Headnotes

John Quincy Adams as Senator and Professor

(September 1801 to July 1809: Massachusetts and Washington, D.C.)

After seven years abroad, John Quincy Adams (JQA) returned to the United States in September 1801. Only 34 years old, he was already one of America’s most accomplished diplomats. During the next eight years he gained experience in Massachusetts and national politics, while also establishing himself as a lawyer and Harvard professor. Ostensibly a Federalist, he most often followed an independent political path. During this domestic interlude, between extensive European diplomatic tours, JQA cemented his reputation as a public servant who held what he perceived to be the national good above personal, regional, or party interests.

JQA reflected in his diary shortly after returning to the United States, “My mode of life has . . . been altogether various.” The next eight years proved to be equally “various.” Soon after his arrival he purchased a home in Boston and relaunched his legal career. He enjoyed ready access to the friends and family from whom he had been separated for so long and regularly visited his parents at Quincy, attended two religious services each Sunday, and met with other men at a Wednesday evening club. His family grew during this period, as eldest son George Washington Adams (GWA) was joined by John Adams (JA2) in July 1803 and Charles Francis Adams (CFA) in August 1807. His foreign-born wife, Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA) adjusted to a new life in the United States while suffering numerous and lengthy periods of poor health.

Louisa Catherine Adams, silhouette by Henry Williams, 1809

Louisa Catherine Adams, silhouette by Henry Williams, 1809

Within months of returning to Massachusetts, JQA accepted the first of a succession of public offices. In February 1802 he was appointed to the Massachusetts bankruptcy commission. Two months later he was elected to the state senate. In November, he narrowly lost an election for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, remarking about his defeat, “I must consider the issue as relieving me from an heavy burden, and a thankless task.” However, in February 1803, the Massachusetts legislature selected him as one of the state’s U.S. senators. He took his seat in October and for the next five years, JQA spent half his time in Washington, D.C. This period of public service proved contentious. The beginning of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe exacerbated political divisions in the United States. The Federalist Party that elected JQA expected him to represent the commercial interests of the Northeast. The Democratic-Republican Party controlled the national government with a majority in both houses of congress and Thomas Jefferson as president. The negotiation and purchase of Louisiana from France took place before JQA took his seat in the Senate. He did not oppose the purchase but attempted to introduce an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to provide for the expansion of new territory. His tacit acceptance of the purchase as important to the national good did not stand well with his Federalist constituents in Massachusetts. This was only one example of the independent stance he took as a senator. Perhaps most damning, in December 1807, he voted in favor of the embargo against European nations—particularly England and France—in retaliation for their aggression toward U.S. merchant ships. The act was extremely unpopular throughout New England, as it prevented American vessels from transporting their goods to overseas markets.

While his political stances frequently failed to find favor in Massachusetts, JQA’s reputation as a scholar led the Harvard Corporation to offer him the position of Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory in June 1805. JQA commented on the appointment in his diary, declaring, “The subject has been mentioned to me, several times in the course of the last three years— But I yet know not whether it will be proper or expedient for me to accept this situation.” When JQA decided to accept the position, he successfully negotiated leave during the school term for the congressional sessions. His lectures proved to be only moderately popular; however, at the request of his students, the thirty-six lectures he delivered between 1806 and 1809 were published in 1810. Ever the scholar at heart, he noted in his diary: “These lectures are the measure of my powers; moral and intellectual. . . . I shall never, unless by some special favour of Heaven, accomplish any Work of higher elevation.”

By the end of 1807 JQA summarized his political position in his diary: “On most of the great national questions now under discussion, my sense of duty leads me to support the administration, and I find myself of course in opposition to the federalists in general.” In January 1808 he even attended the Democratic-Republican caucus that met to select their next presidential candidate. In June of that year the Federalist-controlled Massachusetts legislature voted to replace him for the final year of his Senate term. JQA immediately resigned and temporarily returned to the status of a private citizen.

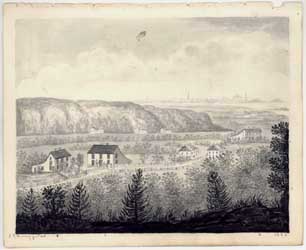

Outside of public service, his life was also complicated during these years. In April 1803 he learned that London bankers Bird, Savage, and Bird, a firm with whom he had resources invested along with much of his father John Adams’ (JA) money, had failed. Months earlier he had noted his concern in his diary when he did not receive an expected communication from the bankers; it left him “in very distressing anxiety for my father’s property in their hands.” On receiving word of the failure, JQA immediately began to sell property to protect his parents and maintain his financial reputation. He took stock of his finances at the end of September 1803: “The transition from the station and means of expence I had previously possessed, could not be agreeable; yet I found it less mortifying than might be expected, and easily reconciled my mind to it— I have practiced all the economy I thought practicable, but have needed still more.” To further cut expenses, he sold his Hanover Street residence in Boston and moved his family to the small Quincy home in which he had been born.

Birthplaces of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, watercolor drawing by Eliza Susan Quincy, 1822

Birthplaces of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, watercolor drawing by Eliza Susan Quincy, 1822

He achieved success as a lawyer during this period. He was active in the Massachusetts courts, but he also practiced before the U.S. Supreme Court. In the early nineteenth century, sitting U.S. senators could also represent clients at the nation’s highest court; this was both convenient and lucrative for JQA. After he resigned his senate seat, JQA divided his time between his Harvard obligations and his law practice. In February and early March 1809, he returned to the national capital to represent John Peck in the case of Fletcher v. Peck before the Supreme Court. While the court did not resolve the case in favor of his client until 1810, before he left Washington, D.C., newly-elected President James Madison presented him with a new diplomatic challenge.

On 6 March President Madison asked him to be the first U.S. Minister to Russia. When it appeared that the nomination would not receive senate confirmation, JQA returned to Boston and his legal and academic life. The Senate, however, finally confirmed his appointment to St. Petersburg on 27 June. Shortly after, he received his commission from Secretary of State Robert Smith. JQA accepted the post “with a deep sense of the stormy and dangerous career upon which I enter.” He made plans to sail for Russia with LCA and CFA and arranged for GWA and JA2 to remain in Massachusetts to continue their education. The Adamses and their two eldest sons would soon be separated for almost six years.

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

John Quincy Adams, Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory: Delivered to the Classes of Senior and Junior Sophisters in Harvard University, Cambridge, 1810; 2 vols.

Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Judith S. Graham, Beth Luey, and others, Cambridge, 2013; 2 vols.

A Traveled First Lady: Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Margaret A. Hogan and C. James Taylor, Cambridge, 2014.

Fred Kaplan, John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, New York, 2014.

“John Quincy Adams,” in John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage, New York, 1956.

William G. Ross, “The Legal Career of John Quincy Adams,” Akron Law Review, 23:415–453 (March 1990).

Allen Sharpe, “Presidents as Supreme Court Advocates: Before and After the White House,” Journal of Supreme Court History, 28:116–144 (June 2003).

Robert R. Thompson, “John Quincy Adams, Apostate: From ‘Outrageous Federalist’ to ‘Republican Exile,’ 1801–1809,” Journal of the Early Republic, 11:161–183 (Summer 1991).