Headnotes

John Quincy Adams as a One-Term President

(March 1825 to December 1829: The Presidency and After)

Inaugurated president of the United States on 4 March 1825, John Quincy Adams (JQA) entered the nation’s highest office at the pinnacle of his career after eight successful years as secretary of state. As president, JQA held a vision for the nation that was rooted in an ambitious reform plan, and he viewed himself as above party politics, the servant of the entire nation. The realities of his presidency, however, meant that his efforts to lead the nation in domestic and foreign policy issues were consistently thwarted by both partisan opposition and his steadfast commitment to principle.

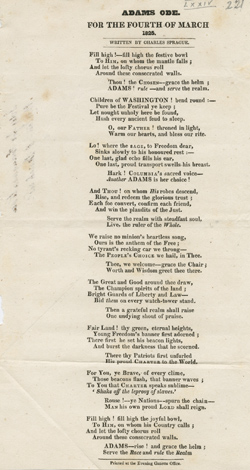

Adams Ode. For the Fourth of March 1825

Adams Ode. For the Fourth of March 1825

The Era of Good Feelings that had characterized the previous decade of American politics devolved into a period of extreme partisanship during JQA’s presidency. Andrew Jackson and his supporters, convinced that the 1824 presidential election had been stolen via the “corrupt bargain,” stymied JQA’s administration whenever possible. Only three days after taking the oath of office, JQA recognized that the opposition in Congress would be his bane. Although most of his cabinet nominations were unanimously approved by the Senate, Henry Clay’s for secretary of state proved an exception. The opposition blamed Clay in large part for Adams’ election. When the Senate confirmed Clay’s appointment by a vote of 27 to 14, JQA correctly recognized this as “the first act of the opposition from the stump, which is to be carried on against the Administration, under the banners of General Jackson.” Almost immediately, the brutal campaign for the 1828 presidential election opened. And, by winning control of the House of Representatives in the 1826 mid-term elections, the Jacksonians gained enough power to make the second half of JQA’s term even more troublesome. Throughout his presidency, sectionalism and states’ rights conflicts exacerbated the partisanship.

JQA’s unwavering resolution to place personal principles above party priorities further impeded his success. As president, JQA had numerous posts to fill, and he could remove officeholders who served at his pleasure, but he refused to replace qualified civil servants with his own political supporters. Members of his cabinet urged the president to dismiss men who were not loyal to the administration, especially those who were openly hostile. JQA stood firm. “To answer merely that it was the pleasure of the President, would be harsh and odious,” and, he continued, “inconsistent with the principle upon which I have commenced the Administration, of removing no person from Office, but for cause.” His refusal to consider patronage appointments plagued him during his four years in the White House. JQA estimated that 80 percent of the custom house officers throughout the union opposed his election. Postmaster General John McLean, a notoriously outspoken member of the opposition, retained his office during JQA’s entire administration because he proved to be a good and talented public servant. This scrupulous stance was a marked contrast to the “spoils system” implemented by Andrew Jackson in 1829, where long-serving public officials were swept out and replaced by loyal partisans. Jackson’s approach, which included McLean’s appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court, galled JQA. “The appointments almost without exception are conferred upon the vilest purveyors of Slander during the late electioneering campaign,” he wrote a year after leaving office.

While many of JQA’s contemporaries identified him as a New England man, JQA was a nationalist. His plans for the economy, which included federal support for internal improvements, like canals, roads, and bridges, coincided with what became known as Henry Clay’s “American System.” JQA’s national vision went beyond these basic improvements. In his first annual message to Congress in December 1825, despite advice from his cabinet, the president called for a national university, an astronomical observatory, and the creation of a Department of the Interior—none of which were approved during his term. The notorious Tariff of 1828, popularly known as the “Tariff of Abominations,” was related to the economic nationalism of his administration. JQA, who makes only passing reference to it in his diary, was not an enthusiastic supporter, but he did sign the tariff into law, igniting an extreme sectional issue that the opposition used to strengthen its hold on the South. This sectional and partisan divide erupted in the fight between the federal government and the state of Georgia over Indian removal.

As a result of settlers’ increasing desire to inhabit Indian lands, treaties between the United States or individual states and Native American tribes during the 1820s mandated the transfer of land from the tribes in return for monetary payments. In the 1825 Treaty of Indian Springs, a minor band of the Creek tribe signed away the tribe’s land in western Georgia. The majority of the tribe refused to recognize the agreement, and the Creeks appealed to the federal government to protect them from the unjust treaty. Their appeal led to a new treaty that was more favorable to the Creek nation. In January 1826 the Treaty of Indian Springs was nullified as fraudulent, and JQA negotiated a new agreement, the Treaty of Washington, which ceded less Creek land than the previous treaty. In response, Georgia governor George Troup continued preparations for the tribe’s removal by sending state surveyors onto Creek land. When the Native Americans defended their rights and threatened the surveyors, Troup responded by ordering state troops onto Indian lands. The governor’s actions created a dilemma for JQA at the start of 1827. Though the president had “no doubt of the right” to send federal troops to Georgia to protect the Creeks,” he questioned “the expediency of so doing . . . To send troops against them must end in acts of violence.” JQA believed this clash of federal versus states’ rights threatened “a dissolution of the Union,” an outcome that was avoided through another treaty. As part of the Treaty of Indian Agency, concluded in November 1827, the Creeks ceded their remaining lands in return for approximately $42,000.

Foreign relations, JQA’s area of greatest experience and renown, proved no more successful during his presidency than his domestic plans. The most remarkable failure, again largely the result of partisan and sectional opposition, concerned the 1826 Pan-American conference held in Panama. South American liberator Simón Bolívar called the meeting to discuss plans for common security in light of European threats to regain control over the former Spanish colonies. Both JQA and Secretary of State Clay believed U.S. participation would be essential to cement relations with the newly independent nations—especially for commercial reasons. This was a natural extension of the Monroe Doctrine, in which JQA helped establish a foreign policy that recognized the independence of these countries and warned against attempts by the European powers to reassert their authority in them. Congressional approval of funds for U.S. participation was delayed so long by partisan bickering that the conference ended before the American delegate arrived.

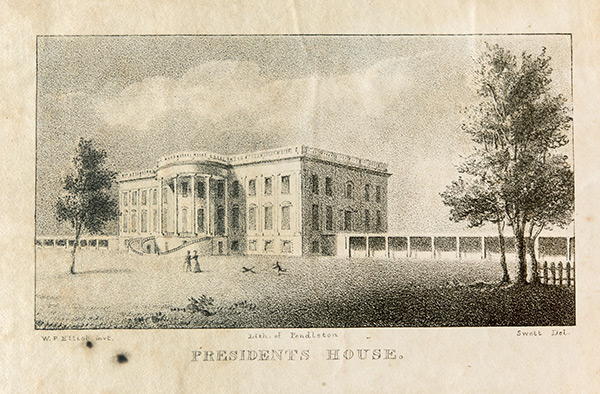

Lithograph of White House affixed inside front cover of JQA’s Diary 37

Lithograph of White House affixed inside front cover of JQA’s Diary 37

Halfway through his term the burden of partisan and sectional conflicts bore down on JQA. “I can scarcely conceive a more harassing, wearying, teazing condition of existence . . . the weight grows heavier from day to day.” JQA had little hope that he would be reelected in 1828, and as the political mudslinging intensified, he seemed more concerned for his reputation than achieving a second term. The Jacksonian press, especially the Richmond Enquirer, attacked the president at every opportunity. “A combination of parties, and of public men, against my character and reputation such as I believe never before was exhibited against any man since this Union existed,” JQA later observed. Eighteen months before the election he conceded to himself: “My own Career is closed— My hopes such as are left to me, are centered upon my children.” On 3 December 1828, Jackson won a landslide victory with 178 to JQA’s 83 electoral votes.

JQA did not attend Jackson’s inauguration. He described his own transition from public to private life, “like an instantaneous flat calm in the midst of a Hurricane.” A month into the new administration, he assessed Jackson’s cabinet. “Among them all there is not a man capable of a generous or liberal Sentiment towards an Adversary,” except John Henry Eaton, “and he is a man of indecently licentious life— They have made themselves my adversaries, solely for their own advancement, and have forfeited the characters of gentlemen, to indulge the bitterness of their self-stirred gall.” Thomas Hart Benton had the principles “of a highway robber,” Martin Van Buren “those of a dirty intriguer,” and John C. Calhoun’s actions were “mere prostitution to popularity.”

As an escape from the myriad duties that consumed JQA’s time during his presidency, he sought to maintain some of the diversions of private life: exercise, reading, and relaxation. During the first year of his presidency, he maintained a vigorous regimen of swimming and walking. Normally a careful person concerned with protecting his health, JQA continually challenged himself to swim farther and longer. After he nearly drowned in a June 1825 accident, he admitted, “This incident gave me a humiliating lesson, and solemn warning not to trifle with danger.” He continued more moderate swimming in hot weather, both in Washington, D.C., and when he returned to Massachusetts. In cold weather he walked, usually in the early morning around Capital Square, and in 1828 and 1829 he frequently rode horseback.

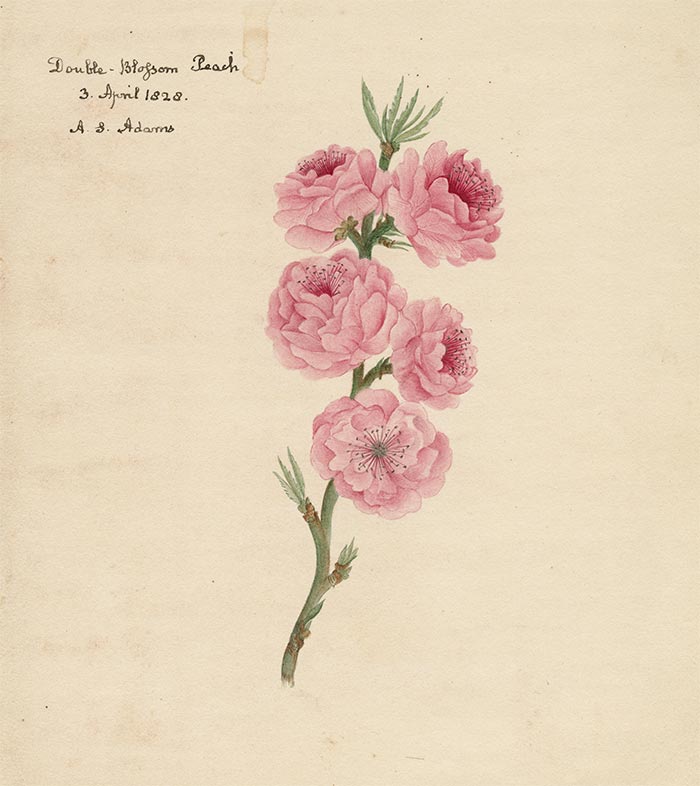

When his social commitments allowed, the president spent his evenings reading, usually commentaries on the Bible, histories, or works from the ancient world such as those by Tacitus and Cicero. He also sought relaxing hobbies, recording frequent references to playing billiards, an innocuous diversion the opposition turned into campaign fodder when they accused JQA, without merit, of being extravagant with public funds because he purchased a billiards table. In the second half of his presidency, JQA’s passion as an arborist surpassed all other pastimes. His interest in the topic was reflected in his reading and in his health regime, where some of his exercise took the form of “garden walks.” To some extent his interest in planting and propagating trees became an escape from the political world.

Watercolor drawing of a “Double-Blossom Peach” by A. S. Adams, 3 April 1828. Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Watercolor drawing of a “Double-Blossom Peach” by A. S. Adams, 3 April 1828. Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

The family’s personal circumstances added to JQA’s burdens during this period. Sixteen months into his term, and in the midst of the failed attempt to secure timely appropriations for the delegation to the Panama conference, JQA received word of his father’s decline and imminent death. On 8 July 1826, while en route to Quincy, he learned of the former president’s passing on 4 July. JQA arrived in Quincy on 13 July. “I was not fully sensible of the change till I entered his bed-chamber, the place where I had last taken leave of him,” JQA reflected. “That moment was inexpressively painful, and struck me as if it had been an arrow to the heart.” His grief was coupled with duty. As JA’s primary beneficiary and one of the estate’s executors, he had extensive work to do to fulfill his father’s wishes regarding bequests. During the next four years, he spent lengthy periods in Massachusetts. He oversaw and assisted with surveys of property he now owned in and around Quincy. He worked to fulfill his father’s wish that funds from the estate be employed for “the Establishment of a School or Academy, for the preparatory Education of youth for the University.” He devoted close attention to the construction of the “Stone Temple” in Quincy, which would contain the tomb and memorial plaque for his father and mother. He took it upon himself to preserve and organize the family’s papers and to write a memoir or biography of JA’s life. The papers were preserved; however, the memoir remained unfinished.

These final duties to his father took place amid the relentless challenges of his presidency and constant concern for his family. His wife, Louisa Catherine (LCA), continued to suffer from bouts of poor health, and in 1828 he begrudgingly accepted the marriage of his son John Adams (JA2) and Mary Catherine Hellen (MCHA), a cousin who had lived in the Adams household for several years. The following year, tragedy struck again with the death of his eldest son, George Washington Adams (GWA).

Word reached JQA on 2 May 1829 that GWA had been lost from the steamboat Franklin during its passage from Providence, Rhode Island, to New York, sometime during the night of 30 April. The news stunned JQA, even though he knew that GWA was troubled. In the fall of 1826, JQA had concluded after a long conversation with his son: “His heart is pure; but his imagination outruns his judgment, his ambition is ardent, and his temper tending too much to despondency; to which his present feeble state of health contributes.” Information JQA gleaned from another Franklin passenger indicated that GWA had become delusional and paranoid during the passage. When his son’s body was recovered in June, JQA traveled to New York to arrange for the disposition of the remains. Afterwards he continued to Quincy where he stayed until December.

Youngest son Charles Francis Adams (CFA) provided one of the few happy family occasions during these years; the young Boston lawyer wed Abigail Brown Brooks (ABA) in September 1829. JQA’s beloved library continued to provide respite. In addition to continuing the family work he had begun in 1826, JQA gathered most of his books in one place for the first time. Included in the renovations of the family’s home at Peacefield, which he believed would be his permanent retirement residence, was extensive shelving for his library. In time his “design was to build in my yard a small Office of Stone, which I might use for a Library and Study.” Despite being occupied in personal and family business, he adjusted poorly to private life. “I distress myself with the consciousness that my few hours of remaining life are slipping away from me unimproved— That my occupations are engrossed for transitory purposes, and that I am losing day after day without atchieving any thing.” JQA found retirement unfulfilling.

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

“1827 Treaty of Creek Indian Agency,” GeorgiaInfo: An Online Georgia Almanac.

Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, New York, 1956.

Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic, Cambridge, 2016.

Mary W. M. Hargreaves, The Presidency of John Quincy Adams, Lawrence, Kans., 1985.

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848, Oxford, 2007.

Fred Kaplan, John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, New York, 2014.

“February 5, 1827: Message Regarding the Creek Indians,” Miller Center Presidential Speeches.

“December 6, 1825: Message Regarding the Congress of American Nations,” Miller Center Presidential Speeches.

Lynn H. Parsons, The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828, Oxford, 2009.

Padraig Riley, “The Presidency of John Quincy Adams,” in A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams, ed. David Waldstreicher, Malden, Mass., 2013.