Headnotes

John Quincy Adams: Old Man Eloquent

(January 1835 to December 1838)

It was during this period of his congressional service that John Quincy Adams (JQA) earned the sobriquet “Old Man Eloquent” for his oratory in the United States House of Representatives. Adams continued to be one of the most respected and influential members of that body, regularly speaking on the controversial issues of the day, including the future of slavery and the annexation of Texas. He also advocated for national scientific and cultural advancement through the creation of the Smithsonian Institution.

From 1835 to 1838, Representative Adams regularly presented antislavery petitions in the House. The majority of these petitions were not, however, requests from constituents in his home district in Massachusetts. As Adams’ reputation for presenting such documents grew, he began to receive petitions from men and women across the United States. These petitions often led to debates over whether they should be received or tabled by the House.

The First Amendment prevented Congress from abridging the rights of Americans “to petition the Government for a redress of grievance,” but in May 1836 a House committee presented a way around this principle when it introduced a resolution that would table all petitions relating to slavery. During the debate on this proposed “gag rule,” JQA sought the floor, but the Speaker of the House James K. Polk refused to recognize him. The House then proceeded to a roll-call vote on the resolution that would silence its members by refusing to formally receive antislavery petitions. Adams recorded his outrage in his diary: “On my name’s being called . . . I answered I hold the Resolution to be a direct violation of the Constitution of the United States—of the Rules of this House and of the rights of my Constituents.” Following the vote, JQA moved to a new phase in his quest to preserve the First Amendment against the onslaught from the southern slavocracy.

Along with his fight against the Gag Rule, JQA opposed the annexation of the republic of Texas. While he had long been an advocate of U.S. territorial expansion, Adams realized that the nation’s delicate sectional balance of power would tip when Texas entered the union as a slave state. Adams read newspaper accounts of the Texas declaration of independence on 2 March 1836 and about the defeat of Texan forces at the battle of the Alamo. When Congress voted to request that President Andrew Jackson send a volunteer militia to assist the Texans, Adams was one of the few congressmen to oppose the measure. His efforts continued during the next presidential administration, and his greatest accomplishment on this issue was a speech that he began on 16 June 1838 and continued during the morning hour of the House’s daily sessions until 7 July. JQA’s long speech, ostensibly against Texas annexation, was also a denunciation of the evils of slavery in American society. Adams’ argument helped persuade President Martin Van Buren to postpone the annexation. JQA subsequently used his notes from the speech to draft a 131-page pamphlet that was printed and widely distributed.

Lithograph of Martin Van Buren (1782–1862).

Lithograph of Martin Van Buren (1782–1862).

As the next congressional session began in January 1837, the Gag Rule was reintroduced and again passed in the House. Adams, however, continued to present the antislavery petitions he received from across the country. His dislike of the institution of slavery and his belief in the inviolability of the First Amendment led him on 6 February to present what he knew to be a fraudulent petition, supposedly drafted by a group of enslaved individuals. Upon Adams’ presentation of this petition, southern congressmen drafted a resolution of censure against him. Three days later Adams took to the House floor to defend the right of petition. In the end the vote of censure against him failed. His focus on the issue was so total that no diary entries are extant from mid-February to the end of March 1837, prompting Adams to comment that it was “the first time for more than forty years” that he had “suffered a total breach in my Diary for several weeks— At one of the most trying periods of my life— The Journals of the House of Representatives of the United States . . . must supply the vacancy.”

Abolitionists lauded John Quincy Adams for his actions, though he did not consider himself a member of their movement. Adams did not relish his role in taking up the antislavery mantle in Congress, yet he believed there was no one else to do it. He recorded in his diary that his involvement with this national issue troubled his family, who “exercise all the influence they possess to restrain and divert me from all connection with the abolitionists, and with their cause.” Caught between his beliefs and his family, Adams stated that “my mind is agitated almost to distraction,” and noted that his own congressional district “is convulsed between the Slavery and abolition questions, and I walk on this edge of a precipice in every step that I take.”

When the 25th Congress convened in December 1837, a new version of the Gag Rule again passed in the House. “When my name was called,” JQA recorded of the vote, “I answered I hold the Resolution to be a Violation of the Constitution of the right of petition of my constituents and of the people of the United States, and of my right to freedom of Speech as a member of this House— I said this amidst a perfect war whoop of order.” The House renewed the Gag Rule in each session until 1844, and Adams continued to protest the practice of preventing the right of petition, unrelenting in presenting the antislavery petitions he received.

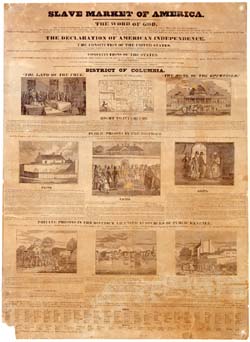

Slave Market of America broadside, issued by American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836

Slave Market of America broadside, issued by American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836

Beyond his stance in Congress, John Quincy Adams learned more about the horrors of slavery through his personal involvement in the cause of Dorcas Allen. Allen was an African-American woman who, though promised emancipation multiple times by her enslavers, did not possess the documents she needed to legally secure her freedom—even though she had been living freely in the District of Columbia for several years. In 1837 Allen and her four children were sold to a slave trader and taken to a slave pen in Alexandria, Virginia. There, Allen murdered the youngest two children and tried to kill the elder two and take her own life. She was tried for murder, pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, and was found not guilty by a jury. After the trial her current enslaver sought to sell Dorcas and her two surviving children; her husband, a free black man named Nathaniel Allen, tried to buy them but had trouble raising the necessary funds to complete the purchase. Adams read about Dorcas Allen’s plight in newspapers, visited her and the children at a slave auction house, and pledged $50 toward the Allens’ freedom. At the end of 1838 Adams offered frank commentary on slavery: “The conflict between the principle of liberty, and the fact of Slavery is coming gradually to an issue. . . . That the fall of Slavery, is predetermined in the counsels of omnipotence, I cannot doubt. . . . But the conflict will be terrible, and the progress of improvement perhaps retrograde before its final progress to consummation.”

The other national issue that consumed JQA during these years was the fate of the Smithson bequest. In December 1835 President Jackson notified Congress that an Englishman named James Smithson had left $500,000 to the United States in his will. “A stranger to this Country, knowing it only by its history,” JQA commented on the unusual bequest in his diary, “that he should be the man to found . . . an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men, is an event in which I see the finger of Providence compassing great results by incomprehensible means.” The House created a special nine-member committee to report on the bequest, with Adams as its chair. In July 1836 the House took up the resulting bill, which stated that the U.S. government would apply the bequest to the founding and endowment of the Smithsonian Institution at Washington, D.C. Adams, however, worried that “this excellent donation will be degraded into a pack of electioneering jobs,” frittered away by the government rather than being held together to create such an institution. As the struggle to found the institution dragged on, he spoke with President Martin Van Buren: “I urged upon him the deep responsibility of the Nation to the world, and to all posterity worthily to fulfil the great object of the Testator— I only lament my inability to communicate half the solicitude, with which my heart is on this subject full.” While Adams personally would have preferred the funds spent on constructing an astronomical observatory, above all he wanted the bequest to go toward the creation of an American research institution.

Photograph of Henry Adams (1838–1918), 1858.

Photograph of Henry Adams (1838–1918), 1858.

JQA and LCA welcomed two additional grandchildren into their family during this period: Charles Francis Adams (CFA2) was born on 27 May 1835 and Henry Adams (HA), the future writer and historian, was born on 16 February 1838. As he moved into his seventies, JQA became increasingly close to his only surviving child, Charles Francis Adams (CFA). He regularly sought his son’s counsel on financial matters and family issues, noting, “all my hopes of futurity in this world are now centered upon him.”

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

Speech of John Quincy Adams, of Massachusetts, upon the Right of the People, Men and Women, to Petition: on the Freedom of Speech and of Debate in the House of Representatives...: on the Resolutions of Seven State Legislatures, and the Petitions of More than One Hundred Thousand Petitioners, Relating to the Annexation of Texas to this Union, Washington, D.C., 1838.

Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, New York, 1956.

Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic, Cambridge, 2016.

Joanne B. Freeman, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, New York, 2018.

Peter Charles Hoffer, John Quincy Adams and the Gag Rule, 1835–1850, Baltimore, 2017.

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford, 2007.

William J. Rhees, editor, The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to its Origin and History, Washington, D.C., 1879.

David Waldstreicher,A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams, Malden, Massachusetts, 2013.