Headnotes

Final Years

(January 1843 to February 1848)

During the last five years of his life John Quincy Adams (JQA) continued to serve in the United States House of Representatives. He witnessed the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War, the settling of the Anglo-American boundary in the Oregon Territory, the repeal of the Gag Rule, and the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution. As his health continued to deteriorate, he recorded in his diary the physical trials of aging, among which was his ability to hold a pen. By September 1845 Adams began to increasingly rely on amanuenses to whom he dictated his diary entries when his own hand failed him.

JQA had opposed the annexation of Texas since it had declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, because he believed it would enter the union as a slave state. His fears were well-grounded. The United States and the Republic of Texas signed a treaty of annexation on 12 April 1844, and President John Tyler submitted the treaty to the Senate for ratification ten days later. In June the vote failed to garner the required two-thirds majority. Pro-Texas congressmen then put forth a joint resolution on annexation, which needed only a majority vote in both houses. In January 1845 JQA spoke against the resolution on the floor of the House and the following month noted that his efforts were “without avail.” “The heaviest calamity that ever befel myself and my country was this day consummated,” JQA wrote when the resolution passed on 28 February.

The annexation of Texas exacerbated tensions between the United States and Mexico. Armed conflict over the disputed border between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers prompted President James K. Polk to declare war on Mexico in April 1846. On 11 May JQA cast one of only fourteen votes in the House opposing the declaration. He described it as a “most unrighteous War” and asserted that the “lying preamble” to the bill, which claimed Mexico initiated the conflict, was “base, fraudulent and false.”

War with Mexico increased concern that unsettled border issues with Great Britain might make the United States vulnerable to another conflict. JQA believed America’s “right, to Latitude 54–40 . . . was perfect, with the single exception of actual possession” and that “Great Britain had no right there, of permanent possession.” He did not think war with Britain was likely, and he opposed a compromise over the Oregon Territory. He again found himself in the minority, when the Oregon Treaty, signed 15 June 1846, placed the boundary at the 49th parallel.

Two of JQA’s pet causes triumphed in Congress during these years. On 3 December 1844 JQA introduced a resolution to repeal the Gag Rule and restore the freedom of petition and debate in the House. After an eight-year battle over the issue that included two attempts to censure Adams, the House finally adopted the resolution that same day. The fate of the Smithson bequest was the second issue JQA championed, having chaired or been a member of the select committee on the Smithsonian fund since 1836. Over the years the funds had been invested in four different states’ bonds, with meager success. Thus, Adams was pleased when, in early 1846, the federal government provided “for the recovery of the money vested in the Stocks of those four States.” After JQA’s decade-long struggle to preserve and apply the funds of James Smithson’s gift to a legitimate scientific purpose, President Polk signed the Smithsonian Bequest Act on 10 August 1846.

Adams experienced the last of his long-distance travels during this period. In the summer of 1843 he visited Quebec, Montreal, and Niagara Falls, in Canada, accompanied by his grandson John Quincy Adams (JQA2), daughter-in-law Abigail Brown Brooks Adams (ABA), and her father Peter Chardon Brooks. When JQA returned to Massachusetts, he ruminated in his diary on the crowds of well-wishers he encountered, noting that the “series of receptions and processions which from the borders of Canada to my quiet retirement at home, have signalized the month of my recent excursion as among the most memorable periods of my life.” During the trip JQA received a letter from Ormsby Mitchel, professor of mathematics and astronomy at Cincinnati College, asking him to speak at the dedication of a new astronomical observatory in Cincinnati, Ohio. Adams’ love of astronomy and his desire to visit that state led him to enthusiastically accept the offer. He spent several months researching and writing his speech. “My task is to turn this transient gust of enthusiasm for” astronomy “into a permanent and persevering national pursuit which may extend the bounds of human knowledge.” JQA left Quincy on 25 October, and after stopping at Buffalo, New York, Erie, Pennsylvania, and Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio, he arrived in Cincinnati on 8 November. The following day he attended the rainy dedication of the observatory, where he read an address at the laying of the cornerstone, and he delivered his oration on 10 November. His trip concluded with a stop in Pittsburgh before arriving in Washington, D.C., on 23 November. JQA again relished the crowds that turned out to meet him, although he found the necessity of contemporaneous public speaking somewhat irksome. “These premeditated addresses by men of the most consummate ability, and which I am required to answer off hand without an instant for reflection, are distressing beyond measure, and humiliating to agony.”

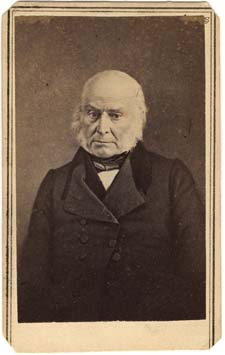

Portrait of John Quincy Adams, painted by Nahum Bell Onthank (1823-1888)

Portrait of John Quincy Adams, painted by Nahum Bell Onthank (1823-1888)

Adams’ age was catching up with him. In 1843 he asked to be excused from the House Committee on Manufactures, believing his health made it “impossible for me to discharge the arduous duties of that office as they ought to be performed.” On 11 July 1844—his 77th birthday—JQA and his wife Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA), “whose arm was linked in mine,” both suffered injuries in a fall from a train platform. Perhaps none of the trials of aging, which Adams described as “a plant withered at the root, a tree, dying downward from the top,” bothered the statesmen as much as his deteriorating handwriting. “I shake like an aspen leaf,” he wrote in September 1845, and by the end of the month he “was compelled to desist from the practice which I had maintained . . . for more than half a century of keeping in my own hand a daily journal of the incidents of my life.” Yet he faithfully continued his diary. JQA utilized as amanuenses his daughters-in-law ABA and Mary Catherine Hellen Adams (MCHA), his granddaughter Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA2), and most frequently his eldest granddaughter, Mary Louisa Adams, whom he called “my proxy.” By the summer of 1846 JQA had regained “partially the use of my right hand.” He continued to pen diary entries on and off for the rest of his life, supplemented, when necessary, by an amanuensis.

In 1845 JQA authored a summation of his life in his diary. He characterized his career in public service as “on the whole highly auspicious.” He identified both his public “friends and benefactors”—George Washington, James Madison, and James Monroe—and his “base, malignant and lying enemies”—namely Andrew Jackson. He placed Thomas Jefferson in his own category, describing him as “a hollow and treacherous friend.” Looking back on the vicissitudes of his life, JQA acknowledged his “advantages of education perhaps unparalleled” among his contemporaries and the “principles of integrity, of benevolence, of industry and frugality, and the lofty Spirit of patriotism and Independence taught me from the cradle.” When he weighed his life “in all its fluctuations,” he found it had “been more successful than I deserved.”

Adams easily won reelection as the representative of the 8th Massachusetts congressional district in November 1846. On the 20th he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while walking in Boston with his friend Dr. George Parkman. For the rest of the year, Adams recuperated at the home of his son Charles Francis Adams (CFA). JQA began to improve by January 1847 and later recounted his convalescence in his diary, penning what he called his“Posthumous Memoir.” The congressman returned to Washington, D.C., on 12 February. When he took his seat in the House the following day, he was greeted by a standing ovation. During the recess that summer, he and LCA celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on 26 July in Quincy. As he returned to Washington, D.C., in the fall he presciently mused: “It seemed to me on leaving home as if it was upon my last great journey.”

John Quincy Adams collapsed on the floor of the House on 21 February 1848. Carried to the office of the speaker, fellow Massachusettsian Robert Winthrop, Adams died there two days later. His funeral was held in the U.S. Capitol on 26 February, with LCA too bereaved to attend and CFA (who had arrived by train from Boston) and MCHA representing the Adams family. A committee of House members accompanied the statesman’s body from Washington, D.C., to Quincy, where he was buried on 11 March. LCA died four years later, on 15 May 1852, and was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. That December they were both reinterred in the crypt of the First Church in Quincy alongside John Adams (JA) and Abigail Adams (AA).

By the time of his death, JQA’s diary encompassed 68 years of entries and contained over 15,000 manuscript pages in 51 diary volumes. JQA himself best summarized the importance of his diary. On 31 October 1846, he wrote, “There has perhaps not been another individual of the human race of whose daily existence from early childhood to four score years has been noted down with his own hand so minutely as mine.”

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Judith S. Graham, Beth Luey, and others, Cambridge, 2013; 2 vols.

Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, New York, 1956.

Nina Burleigh, The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum, The Smithsonian, New York, 2003.

Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic, Cambridge, 2014.

Peter Charles Hoffer, John Quincy Adams and the Gag Rule, 1835–1850, Baltimore, 2017.

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford, 2007.

David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War, Columbia, Missouri, 1973.