Headnotes

John Quincy Adams as Secretary of State and Presidential Candidate

(March 1821 to February 1825: President James Monroe’s Second Term)

Throughout the four years of James Monroe’s second presidential term, John Quincy Adams (JQA) continued to serve as secretary of state. It was during these years that JQA scrutinized U.S. policy regarding the revolutions occurring in Latin America and developed the strategy that became known as the Monroe Doctrine. While his duties as secretary of state and the constant stream of visitors to his office kept JQA busy, almost as soon as Monroe won reelection the contest for who would attain the presidency in 1824 occupied much of JQA’s time and attention.

Charles Kennedy Burt, 1870

While JQA kept a close eye on the political landscape, he still had to perform the duties of secretary of state. Relations with the major powers continued much as they had during the first Monroe administration. Stratford Canning, British minister to the U.S., continued to press for cooperation in suppressing the Atlantic slave trade. JQA could only listen, not act, as powerful slave-holding interests in America made serious consideration impossible. Other Anglo-American issues included resolution of the border with Canada and access to British West Indian ports. One important area of agreement between Britain and the U.S. concerned Latin America.

Charles Kennedy Burt, 1870

While JQA kept a close eye on the political landscape, he still had to perform the duties of secretary of state. Relations with the major powers continued much as they had during the first Monroe administration. Stratford Canning, British minister to the U.S., continued to press for cooperation in suppressing the Atlantic slave trade. JQA could only listen, not act, as powerful slave-holding interests in America made serious consideration impossible. Other Anglo-American issues included resolution of the border with Canada and access to British West Indian ports. One important area of agreement between Britain and the U.S. concerned Latin America.

Lithograph by Nicolas-Eustache Maurin for Messers Dogget, after painting by Stuart, ca. 1828 The success of the republican experiment in the United States threatened the conservative European powers. As early as 28 November 1821, the prescient secretary of state recognized: “They all hated us for our principles— They dreaded the effect of our example; the standing refutation of their doctrines in our prosperous condition, and the danger to themselves in our constantly growing power.” Just as during the previous four years, the rapid decline of the Spanish-American empire and the rise of revolutionary, and subsequently independent, Latin American states provided JQA with his most important diplomatic challenge. After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, conservative European powers, led by Alexander I of Russia, formed the Holy Alliance to stop the spread of republican government and reestablish divine right monarchy. In 1822 the Holy Alliance defeated a republican movement in Spain. They next threatened to return the newly independent Latin American states to colonial status. About the same time, the Monroe administration recognized Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru as independent nations. The renewal of any European colonial power in the western hemisphere was antithetical to American republican ideals and potentially harmful to national security and commerce.

Lithograph by Nicolas-Eustache Maurin for Messers Dogget, after painting by Stuart, ca. 1828 The success of the republican experiment in the United States threatened the conservative European powers. As early as 28 November 1821, the prescient secretary of state recognized: “They all hated us for our principles— They dreaded the effect of our example; the standing refutation of their doctrines in our prosperous condition, and the danger to themselves in our constantly growing power.” Just as during the previous four years, the rapid decline of the Spanish-American empire and the rise of revolutionary, and subsequently independent, Latin American states provided JQA with his most important diplomatic challenge. After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, conservative European powers, led by Alexander I of Russia, formed the Holy Alliance to stop the spread of republican government and reestablish divine right monarchy. In 1822 the Holy Alliance defeated a republican movement in Spain. They next threatened to return the newly independent Latin American states to colonial status. About the same time, the Monroe administration recognized Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru as independent nations. The renewal of any European colonial power in the western hemisphere was antithetical to American republican ideals and potentially harmful to national security and commerce.

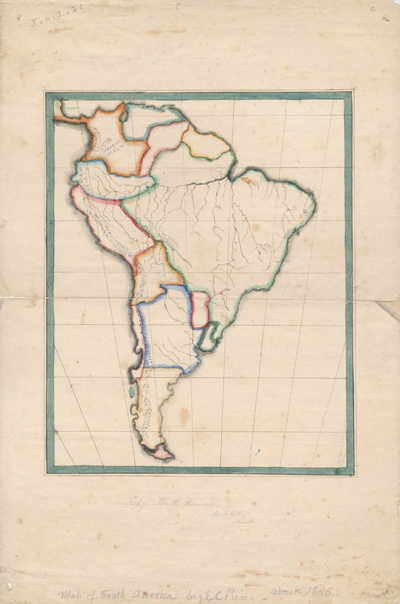

Manuscript map of South America circa 1840

Manuscript map of South America circa 1840

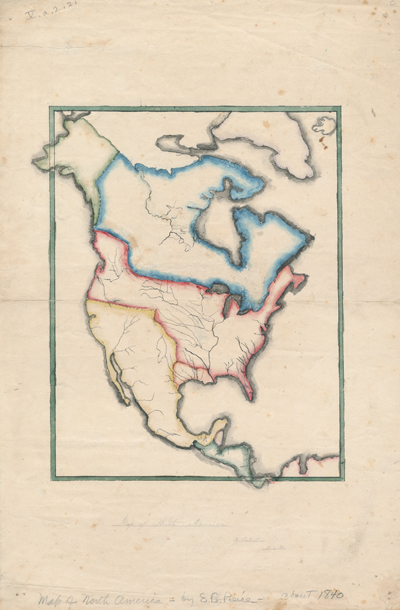

Manuscript map of North America circa 1840

Manuscript map of North America circa 1840

British foreign minister George Canning, knowing it was of interest to both Britain and the U.S. that the Holy Alliance not reassert colonial control in Latin America, proposed a joint Anglo-American statement. During October and November 1823, JQA worked to convince the president and the cabinet to make its own unilateral statement. He summed up his reasoning in his 7 November diary entry; while British and American interests in thwarting the Holy Alliance coincided, “It would be more candid as well as more dignified to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a Cock-boat in the wake of the British man of War.” Despite some opposition in the cabinet and former president Jefferson’s advice against it, a hesitant Monroe approved the idea. Over the next weeks, JQA drafted the portion of the president’s 2 December annual message to Congress that became known as the Monroe Doctrine. On 27 November, as a diplomatic courtesy, JQA informed Russian minister Baron Van Tuyll de Serooskerken of the contents of the policy. He commented in his diary: “I considered this as the most important paper that ever went from my hands.”

The period popularly known as the Era of Good Feelings (1817–1825) ended during the 1824 presidential campaign. With the demise of the Federalist Party, the single national Democratic-Republican Party did not result in political unity. Sectional and other divisions, as well as the personal competition of the men seeking to succeed President Monroe, made this a particularly contentious period. The election campaign began in 1821, and during the next three years several potential candidates were eliminated until only four remained. In addition to JQA, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford of Georgia, congressman and sometime Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky, and General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee stayed in the contest. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, an early aspirant, declared for the vice presidency after Jackson’s popularity in the South surpassed his. Throughout the campaign supporters of the other candidates assailed JQA’s character and reputation. While he responded on occasion, usually he heeded the advice he recorded in his diary on 31 December 1821: “To answer newspaper accusations would be an endless task. The tongue of falsehood can never be silenced: and I have not time to spare from public business to the vindication of myself.” Throughout the campaign, he kept his own counsel. On 11 July 1822, his 55th birthday, he lamented: “I need advice very much; but have no one to advise me.”

One of the great changes that took place during the 1824 election campaign concerned the nominating process. There is no provision in the Constitution for the nomination of presidential candidates, and since 1796 caucuses of the political parties’ congressional delegations met informally and selected their candidates without direct input from the voting public. As there remained only one viable political party in 1824, it was presumed the congressional nominee would almost certainly be elected. JQA condemned the caucus system on 9 May 1822, referring to the two houses of Congress as “the Pretorian Guards, who will in substance if not in form set up the Empire at Auction.” Throughout 1823, several states passed resolutions against the caucus system and allowed presidential electors to be chosen by popular vote rather than by state legislatures. However, the caucus met before the election and selected Crawford, while various state legislatures nominated JQA, Jackson, and Clay.

The vote divided among the four candidates; no one obtained the majority necessary for election. Jackson led the popular as well as the electoral vote, JQA came in second in both, Crawford finished a distant third, and Clay fourth. The 12th Amendment provided that, if no one received a majority, the candidates with the three highest electoral votes could continue the contest in the House of Representatives. There each state, regardless of population, had one vote, and a majority of the states was necessary for election. Between the counting of the electoral votes on 1 December 1824 and the vote in the House on 9 February 1825, the candidates attempted to coalesce support in order to gain the majority. Clay decided to throw his support behind JQA, whose national outlook most resembled his own. This move proved decisive. JQA took thirteen states, Jackson seven, and Crawford four. Soon after, JQA named Clay his secretary of state, and Jackson’s supporters accused them of a “corrupt bargain.”

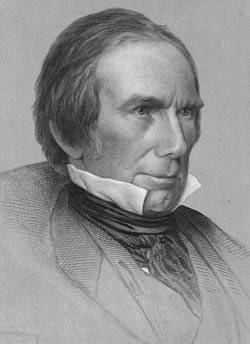

Engraving of Henry Clay JQA’s family remained a concern. His wife, Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA), continued to be one of the capital’s most remarkable hostesses and a great asset to the socially challenged presidential candidate. Despite frequent illness, she persisted with her biweekly levees. On 8 January 1824, the Adamses held a great ball in honor of General Andrew Jackson, ostensibly to celebrate the anniversary of his 1815 victory at New Orleans. The ulterior motive was to promote JQA’s popularity and presidential candidacy. The ball was held at their F Street home, purchased 30 March 1821. While they moved several times after 1825, they would return to that house in 1838.

Engraving of Henry Clay JQA’s family remained a concern. His wife, Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA), continued to be one of the capital’s most remarkable hostesses and a great asset to the socially challenged presidential candidate. Despite frequent illness, she persisted with her biweekly levees. On 8 January 1824, the Adamses held a great ball in honor of General Andrew Jackson, ostensibly to celebrate the anniversary of his 1815 victory at New Orleans. The ulterior motive was to promote JQA’s popularity and presidential candidacy. The ball was held at their F Street home, purchased 30 March 1821. While they moved several times after 1825, they would return to that house in 1838.

JQA continued to worry about his sons. The youngest, Charles Francis Adams (CFA), matriculated at Harvard in 1821 after narrowly passing his entrance examination in Latin. JQA feared that some personal grudges held against him by members of the faculty might affect his sons at college. However, he discovered that his eldest son, George Washington Adams (GWA), ranked 30th in his class and that his middle son, John Adams (JA2), ranked 45th in his. On 30 September, JQA recorded “a sleepless Night— Cares for the welfare and future prospects of my children; mortification at the discovery how much they have wasted of their time at Cambridge . . . I find them all three, coming to manhood, with indolent minds.” On 2 May 1823 JA2 was expelled from Harvard; his and GWA’s subsequent tragic lives and careers would validate their father’s concern.

While a successful statesman and diplomat, JQA proved less than prudent as an investor. He occasionally made mistakes in trusting family and friends with his money and investments. In the summer of 1823 he purchased Columbia Mills, a water-powered flour mill on Rock Creek north of Georgetown. LCA’s cousin George Johnson, who was near bankruptcy, convinced JQA to make the purchase. JQA sold government bonds and mortgaged the F Street property to raise the money. A year later, on 25 August 1824, he concluded that the first year “has been a total and a severe disappointment; and I have no reason to expect any thing better from the second.” The mill proved to be a continuing drain on his resources and remained a financial liability for the rest of his life.

Despite his public concerns and private burdens, JQA did enjoy diversions and regular recreation that he noted throughout his diary. He attended the theater frequently and critiqued the plays and performers. When the theater season ended in the fall, he spent more time reading, writing, and playing chess. He continued a vigorous physical regimen throughout the year. During cool weather he walked early each morning, noting in his diary the route, destination, or time spent in perambulations. In warm weather he swam; JQA pursued swimming with a greater passion than any other exercise and sometimes pushed himself to extremes. On 19 June 1823 he reflected, “I follow this practice for exercise, for health, for cleanliness and for pleasure.” However, his physician “and all my friends think I am now indulging it to excess. . . . I must now limit my fancies for this habit, which is not without danger.”

These four years are among the most eventful in JQA’s long public life. At the peak of his power and influence as a statesman, his diary is uneven in its revelation of the man’s thoughts and views. At times it is expansive and detailed, while at other moments, especially when pressed for time, he merely records a brief sketch of the diurnal events. The diary proved both a joy and a burden. On 20 March 1821, he admitted to himself: “Had I spent upon any work of Science or Literature, the time employed upon this Diary, it might perhaps have been permanently useful to my Children and my Country— I have devoted too much time to it— My physical powers sink under it.”

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

A Traveled First Lady: Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Margaret A. Hogan and C. James Taylor, Cambridge, 2014.

Catherine Allgor, Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government, Charlottesville, Va., 2000.

Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy, New York, 1949.

Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic, Cambridge, 2016.

Robert Pierce Forbes, The Missouri Compromise and its Aftermath, Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007.

“The History of the Columbia Mills,” Smithsonian Institution: Preservation, https://www.si.edu/ahhp/h_mills#85

Fred Kaplan, John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, New York, 2014.

James E. Lewis, Jr., John Quincy Adams: Policymaker for the Union, Wilmington, Del., 2001.

Ernest R. May, The Making of the Monroe Doctrine, Cambridge, 1975.

Paul Nagel, John Quincy Adams, New York, 1997.

Lynn Hudson Parsons, John Quincy Adams, Madison, Wis., 1998.

“Presidential Election of 1824: A Resource Guide,” The Library of Congress: Web Guides, http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/elections/election1824.html

James Traub, John Quincy Adams: Militant Spirit, New York, 2016.

John Quincy Adams and the Politics of Slavery, ed. David Waldstreicher and Matthew Mason, New York, 2017.