Headnotes

The Amistad Case: John Quincy Adams Returns to the Supreme Court

(January 1839 to December 1842)

During his second decade as a member of the United States House of Representatives, John Quincy Adams (JQA) continued to be an outspoken opponent of the pro-slavery forces’ grip on the nation. Leading abolitionists recognized Adams’s powerful oratory, masterful knowledge of the U.S. Constitution, and frustration with southern domination of the federal government. They consulted him on the case of the Spanish slave ship Amistad. The complicated issues of the case intrigued the statesman, and he agreed to represent the African defendants before the U.S. Supreme Court. This complex legal, diplomatic, and humanitarian contest was the most important slavery-related case before the court until Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857. Adams considered the methods employed by more extreme abolitionists counterproductive, yet John Tyler’s ascension to the presidency in 1841 pushed Adams to be more assertive in his opposition to slavery.

In July 1839, fifty-three Africans revolted aboard the Spanish slave ship Amistad as they were being transported by their enslavers from Havana to another Cuban port. During the revolt, the Africans killed the ship’s captain and another crew member, and they demanded to be returned to Mendiland (now Sierra Leone). Because the Africans possessed limited navigational knowledge, the remaining Amistad crew were able to divert the vessel from its course. On 24 August a U.S. revenue cutter seized the Amistad off Long Island and brought it into the port of New London, Connecticut. The Africans were imprisoned at New Haven, Connecticut, although charges of murder and piracy were quickly dropped. Instead, the case centered around property rights. First decided in the U.S. District Court at Hartford, Connecticut, the case contained several elements, central to which was the legal status of the Africans. The captain of the revenue cutter claimed salvage rights for taking the Amistad; the Spaniards who had enslaved the Africans claimed them as their property; and the Spanish government demanded that the vessel and the human cargo be returned to a Cuban court. The Van Buren administration, seeking to avoid an international conflict and end another slavery-related issue, wished to return the vessel, the Africans, and the whole case to the Spanish authorities.

In January 1840, the U.S. District Court ruled that the Africans were not slaves. They had been taken from their African homeland in 1838, long after an agreement—to which Spain was a signatory—ended the legal importation of slaves to the western hemisphere. Thus, neither the Spaniards, who claimed the Africans as property, nor the Spanish authorities had any legitimate rights in the affair. The captain of the revenue cutter’s salvage claim was sustained. In April 1840, the U.S. Circuit Court, ruling on Attorney General Henry Dilworth Gilpin’s appeal, upheld the district court’s decision.

While he had agreed to offer opinions and advice on the Amistad case as early as September 1839, JQA did not take a formal role until a year later. Abolitionists Ellis Gray Loring and Lewis Tappan visited the former president at Quincy on 27 October 1840 and convinced him to join the Amistad defense team when the government appeal went before the Supreme Court. JQA recorded his initial reluctance: “I endeavoured to excuse myself upon the plea of my age and inefficiency—of the oppressive burden of my duties as a member of the House of Representatives, and my inexperience after a lapse of more than thirty years . . . before judicial tribunals.” However, the abolitionists proved persuasive. “They urged me so much and represented the case of those unfortunate men as so critical, it being a case of life and death, that I yielded.”

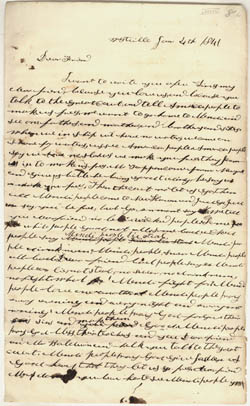

Letter from Kinna to John Quincy Adams, 4 January 1841

Letter from Kinna to John Quincy Adams, 4 January 1841

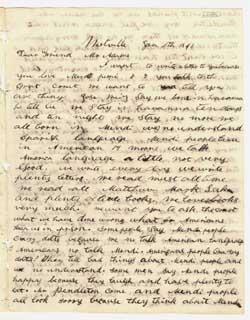

Letter from Kale to John Quincy Adams, 4 January 1841

Letter from Kale to John Quincy Adams, 4 January 1841

The trial began on 22 February 1841. JQA assisted Roger Sherman Baldwin, the defense counsel who had seen the case through the district and circuit courts. Attorney General Gilpin presented the government’s appeal. Baldwin, in support of the lower courts’ decisions, completed his arguments on 23 February. JQA observed that his co-counsel’s reasoning “was powerful, and perhaps conclusive;” however, Baldwin “spoke in cautious terms to avoid exciting Southern passions and prejudices, which it is our policy as much as possible to asswage and pacify.” JQA opened his defense on 24 February and while “deeply distressed and agitated till the moment when I rose,” he “spoke four hours and a half, with sufficient method and order to witness little flagging of attention, by the judges or the auditory.” Pleased with his performance, he modestly assessed: “I did not I could not answer public expectation—but I have not yet utterly failed.” After a delay in the proceedings, occasioned by the death of Associate Justice Philip Pendleton Barbour, JQA returned to the court on 1 March to conclude his argument on behalf of the Amistad Africans. He spoke for another four hours. Gilpin closed the government’s case the following day. The court’s opinion, delivered on 9 March, affirmed the decision of the lower courts by a seven to one vote. The Africans were free.

During this period of JQA’s public service, the congressman witnessed three different presidential administrations. Elected in 1840 to succeed Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison died after only a month in office. Vice President John Tyler, a strident proslavery Virginian, was elevated to the presidency on 4 April 1841. He refused to requisition a navy vessel to return the now-free Amistad Africans to their homeland. Instead, Abolitionists raised private funds for the voyage. Before their departure in November 1841, JQA received a Bible “signed by Cinque, Kinna and Kale for the 35 Mendian Africans of the Amistad.” This “Mendi Bible” remains in the Stone Library at Adams National Historical Park in Quincy, Massachusetts.

JQA continued to present anti-slavery petitions in Congress, despite various iterations of the Gag Rule being in place. On 24 January 1842, Adams presented a petition from citizens of Haverhill, Massachusetts, asking Congress to immediately adopt measures to peacefully dissolve the United States. Virginia congressman Thomas Walker Gilmer declared JQA’s action treasonable and called for his censure. During the censure hearing in early February, JQA not only ably defended himself but “brought to light the conspiracy among the Southern Members of the Committee of foreign Affairs to displace me as Chairman.” The censure resolution was tabled on 7 February.

Adams realized that age (he was seventy-three when he appeared before the Supreme Court) diminished his physical and mental capacities. However, a few weeks after the Amistad decision, he acknowledged his unwavering dedication to public service. “More than 60 years of incessant active intercourse with the world has made political movement to me as much a necessary of life as atmospheric air. . . . And thus while a remnant of physical power is left me to write and speak, the world will retire from me before I shall retire from the world.” He seemed energized by his role in the Amistad case and also perhaps by his opposition to the administration of John Tyler, whom he described as “a political sectarian of the Slave-driving, Virginian Jeffersonian school— Principled against all improvement— With all the interests and passions, and vices of Slavery rooted in his moral and political constitution.” Adams’ public stature varied dramatically in the North and South. “Not a day passes but I receive Letters from the North and sometimes the West asking for an autograph, and a scrap of poetry or of prose, and from the South almost daily Letters of insult, profane obscenity and filth— These are indexes to the various estimation in which I am held in the free and servile sections of this Union.”

His reputation as an author and orator on topics as far ranging as China, society and civilization, temperance, and faith, made him one of the most sought-after lecturers of the era. This popularity overwhelmed him. “The Lecture Mania is yet more annoying. . . . not a day passes but I receive invitations to deliver Lectures.” He declined most requests and avoided lecturing on political issues. Ostensibly a Whig statesman, JQA refused to take part in party conventions or address political meetings, believing, “since I had held myself the Office of the President of the United States, I felt it my duty to abstain from all personal interference in the Presidential election.”

Away from public life, his households in Quincy and Washington, D.C., consisted of wife Louisa Catherine Adams (LCA), daughter-in-law Mary Catherine Hellen Adams (MCHA), and granddaughters Georgeanna Frances (Fanny) Adams and Mary Louisa Adams. Grief struck when nine-year-old Fanny died on 20 November 1839 after a protracted illness, JQA recalled, “the agonies of our separation from that adored child, the pang of which will go with me to my dying day,” and that her “sufferings . . . from hour to hour for weeks and months in succession disqualified me for all energetic action.”

In 1839 JQA compiled a list of thirty-four sittings he had done for various artists throughout his life. By 1842, advances in rudimentary photography added a new form of portrait sitting. On 27 September he went to John Plumbe’s Daguerrian Gallery in Boston to have his photograph taken. This first experience with the new technology proved unsatisfactory. “They kept me there an hour and a half, and took seven or eight impressions, all of them very bad.” Each photo required the sitter to remain perfectly still and focused on an object. Adams could not keep his eyes open. “I dosed and the picture was asleep— I gave it up in despair.” None of these first photographs are extant, although Adams would again sit for a photographer the following year.

Selected Bibliography for Further Reading

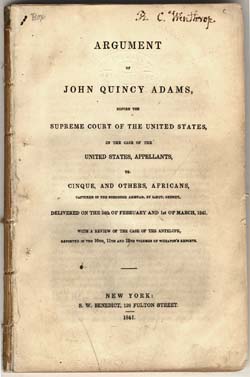

John Quincy Adams, Argument of John Quincy Adams, Before the Supreme Court of the United States, in the Case of the United States, Appellants vs. Cinque, and Others, Africans, Captured in the Schooner Amistad, by Lieut. Gedney, Delivered on the 24th of February and 1st of March, 1841, New York, 1841.

Amistad, Directed by Stephen Spielberg, DreamWorks Pictures, 1997.

John Warner Barber, A History of the Amistad Captives: Being a Circumstantial Account of the Capture of the Spanish Schooner Amistad, by the Africans on Board; Their Voyage, and Capture near Long Island, New York, New Haven, Connecticut, 1840.

Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, New York, 1956.

Peter Charles Hoffer, John Quincy Adams and the Gag Rule, 1835–1850, Baltimore, 2017.

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford, 2007.

Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy, New York, 1987.

Fred Kaplan, John Quincy Adams, American Visionary, New York, 2014.

Marcus Rediker, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, New York, 2012.

David Waldstreicher and Matthew Mason, John Quincy Adams and the Politics of Slavery, New York, 2017.