Online: Object of the Month

"The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America."

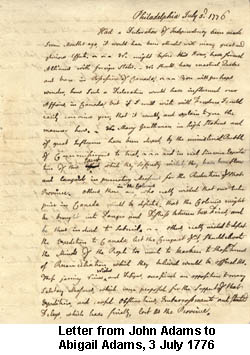

In a letter to Abigail Adams written on 3 July 1776 from Philadelphia, John Adams predicts exactly how "succeeding Generations" of Americans would celebrate Independence. He was right about everything except the date:

"succeeding Generations" of Americans would celebrate Independence. He was right about everything except the date:

I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by Solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and lluminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

What John Adams was referring to was not what we celebrate today, the Declaration of Independence, but, as he put it in yet another letter to Abigail written the same day (3 July 1776):

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony "that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do."

Although in a famous letter to her husband written earlier that spring, Abigail Adams complained, "I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you," John Adams wrote to her continuously, sometimes more than once during the course of his long work days, so she was intimately aware of events in Philadelphia and felt free to advise him on the actions he should take as the Congress moved towards "declar[ing] an independancy."

"A Declaration setting forth the Causes…"

John Adams seems to have understood more clearly than any other member of the Continental Congress the momentous importance of the vote for Independence, but at the time, he appeared to attach less importance to the public proclamation of the vote. In his second 3 July letter to Abigail, he informs her in a matter-of-fact way that she "will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell'd Us to this mighty Revolution, and the Reasons which will justify it…."

This was not due to any lack of personal knowledge of the contents of the Declaration. Adams served with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston on the Committee of Five that the Continental Congress appointed to draft the Declaration that would proclaim Independence. Jefferson prepared a rough draft that was revised by the Committee with stylistic suggestions by Adams and Franklin. Congress voted to adopt a resolution for Independence on 2 July 1776, and continued to revise the Declaration of Independence until 4 July, when it authorized the Committee to publish the corrected text. Printed copies of the Declaration began to circulate on 5 July and it was read aloud in Philadelphia on 8 July and in Boston ten days later on 18 July 1776.

Neither a "momentous" resolution of Independence, nor an eloquently-worded declaration alone would secure Independence for the American colonies. On 3 July 1776, the same day that John Adams twice wrote to Abigail, an immense British armada began landing troops on Staten Island in New York Harbor. The next and most dangerous phase of the Revolutionary War was about to begin.

Summer exhibition: 2 July through 31 August, 2012

To mark the anniversary of Independence—no matter which day we choose to celebrate it—the Massachusetts Historical Society mounted a summer exhibition, “The Most Memorable Day in the History of America: July 2, 1776,” consisting of John Adams’s 3 July letter, described here, and digital facsimiles of manuscript copies of the draft of the Declaration of Independence in the hands of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, together with a copy of the first printing of America’s birth announcement. These documents tell the story of the creation of the Declaration and show how individuals intimately involved in a "momentous" historical event may not fully understand or appreciate what has taken place, or how it will be understood by future generations.

"The Most Memorable Day in the History of America: July 2, 1776" was on display through August 31, 2012, Monday-Saturday, 10:00 AM-4:00 PM.

Further reading:

Boyd, Julian P. The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text. Rev. ed. Washington: Library of Congress in Association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1997.

Declarations of Independence. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003.

McCullough, David. John Adams. Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Related Items

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United ...

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United ...

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy by Thomas Jefferson, 1776]

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy by Thomas Jefferson, 1776]

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, ...

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, ...

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March - 5 April 1776

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March - 5 April 1776

Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776

Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 21 July 1776

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 21 July 1776

Abigail Adams described hearing the Declaration of Independence read from the balcony of the Old State House. See painting below:

Printings of the Declaration

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United ...

The Continental Journal and Weekly Advertiser

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United ...

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United ...

Reactions to the Declaration

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 21 July 1776

John Rowe diary 13, 18-20 July 1776, page 2197

Letter from Henry Alline to his brother and sister, 19 July 1776

Additional Online Content

Thomas Jefferson's memorandum book, page 11

A Declaration by the Representatives of the United Colonies of North-America, ...

By the Great and General Court of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay. A Proclamation ...

More information on the events leading up to the Declaration of Independence is available on the Massachusetts Historical Society's web feature, Coming of the American Revolution.

Warning: file_put_contents(/var/www/html/features/juniper/cache/july2012--^var^www^html^^features^bbcms_templates^voodoo^article^.cache): failed to open stream: Permission denied in /var/www/html/features/juniper/bbcms_class.php on line 268