Collections Online

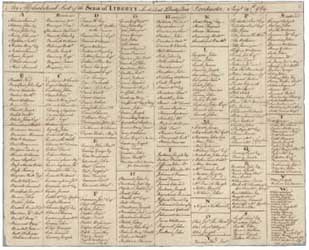

"An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty who din'd at Liberty Tree, Dorchester"

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- MHS 225th Anniversary

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Object of the Month ]

This manuscript lists the 355 Sons of Liberty who gathered at Lemuel Robinson's tavern in Dorchester on 14 August 1769 to commemorate the fourth anniversary of the Stamp Act Riots in Boston, Massachusetts. The list was compiled by William Palfrey and indicates that 300 of these men stayed to dine.

Stamp Act Riots

In the spring of 1765, news came to Boston that Parliament intended to impose a stamp tax on the colonies. Legal forms, financial records, newspapers and pamphlets, even playing cards would require the purchase of stamped paper. The Stamp Act was protested everywhere in colonial America, but it was greeted by violent resistance in Boston. Although the act would not go into effect until November 1765, on 14 August, opponents gathered at a great elm that soon would come to be known as the Liberty Tree. A well-organized mob marched upon the office and home of Andrew Oliver, who had been appointed the stamp master for Massachusetts. The next day, Oliver resigned the office that he had not yet taken up. Twelve days later, on 26 August, a much more violent and ill-disciplined mob destroyed the elegant home of Oliver's brother-in-law Thomas Hutchinson, the lieutenant governor and chief justice of Massachusetts, who was thought to secretly support the Stamp Act. Although the violence of the attack on Hutchinson's mansion shocked leaders of the patriot movement in Boston, the combination of popular agitation and threats of violent resistance made it impossible to enforce the Stamp Act anywhere in America. The royal government repealed the act in the spring of 1766.

Remembering the Riot

In the years after 1765, Bostonians began to commemorate the events of August 1765. They chose 14 August (the date of the first riot) as the date for their celebration, rather than 26 August, the anniversary of the later and more controversial sacking of the Hutchinson mansion. In 1767, sixty people gathered to mark the anniversary and drink to the king's health; celebrants were careful to distinguish between their loyalty to the king and their resistance to parliamentary interference in colonial affairs. Each year the anniversary celebration increased in size. In 1768 there was a parade and large gathering at the Liberty Tree in Boston, and in 1769, according to newspaper accounts, an enormous throng gathered again at the Liberty Tree in Boston where, at 11:00 AM, they drank fourteen toasts (to commemorate the 14th of August) and then "repaired" to the "Liberty-Tree-Tavern," Colonel Lemuel Robinson's tavern in Dorchester, just outside of Boston, where 300 of 355 present dined together under a tent pitched for the purpose, with "a variety of colours" (flags) flying. They were entertained with music, including John Dickinson's "Liberty Song," "mimickry" by Nathaniel Balch, the firing of cannon, and after dinner had forty-five more toasts. The number forty-five referred to a famous 1763 issue of the John Wilkes's radical English newspaper, the North Briton that had made Wilkes a hero to the cause of freedom of speech in England and America. Except for the first, "indispensable" toast to the "King, Queen, and Royal Family," each gentleman present was allowed to drink as moderately as he was inclined, and John Adams, who was present, was surprised by the temperance of the participants. About 5:00 PM, the diners left Robinson's Tavern in a procession that extended more than a mile in length and returned to Boston and circled the State House (Boston's present-day Old State House) before retiring to their homes.

Who Were "True Sons of Liberty"?

The "Sons of Liberty" in Boston and elsewhere in colonial America had grown out of the associations organized to resist specific actions (the Stamp Act) or a more general resistance to parliamentary authority. The term "Sons of Liberty" was much older, referring more generally to people (there were "Daughters of Liberty" as well), who espoused their freedoms under the English Constitution. In Boston, the members of the "Loyal Nine," a social club that helped organize the events of 14 August 1765, soon came to be known as the "Sons of Liberty." The men who met and dined on 14 August 1769 included many of the members of the inner circle of the Sons of Liberty, but also a much larger number of men who opposed to the Stamp Act, but who had not necessarily taken any part in the organized protests and riots.

The list that William Palfrey compiled of the men who gathered in Dorchester includes a "Who's Who" of the patriot (and future revolutionary) leadership of Boston: John and Samuel Adams, Benjamin Church, John Hancock, James Otis, Joseph Warren, and Thomas Young. While the Boston Evening-Post described the event as "the day of the Union and firmly combined association of the TRUE SONS OF LIBERTY in this Province," the attendees were for the most part members of the Boston business establishment (a third of the men listed were merchants), together with lawyers, physicians, schoolmasters, members of the legislature, and militia officers, leavened with skilled craftsmen (Thomas Crafts and Paul Revere, for example), shopkeepers (Stephen Cleverly--a member of the Loyal Nine--and Harbottle Dorr), printers (Benjamin Edes, another member of the "Nine," and Thomas Fleet), a half-dozen visitors to Boston invited to the occasion, and a large number of individuals so cryptically described, or bearing such common names, that it would be difficult to positively identify them. [Palfrey's list is assembled in rough alphabetic order--all the attendees are grouped by the first letter of the last name. A large digital image and a literal transcription of the document is available via the links above. A strict alphabetical list of all the names is also available.(Link to display with formatting forthcoming!)]

In his diary, John Adams fretted that if he had not been present he might have been suspected as "not hearty in the Cause," and not everyone who was listed as a "Son of Liberty" in 1769 later supported the move from resistance to revolution. Political differences would divide brothers who dined together (Samuel and Josiah Quincy) and fathers from sons (John and James Lovell, and John and John Gore, Jr.). Some men present left Boston or died before they had to decide which way to jump: the Hon. Royall "Pug Sly" Tyler, whom Governor Hutchinson described as "sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other," died from either overindulgence or medical malpractice in 1771. Others would break with the patriots, but stay: Dr. James Pecker was an active member of the Sons of Liberty, but refused to serve in the Revolution and was threatened with arrest, but he remained an honored member of the medical establishment in post-war Boston.

William Palfrey

As John G. Palfrey noted in his biographical sketch of his grandfather, William Palfrey, his subject "was officially brought into intimate relations with some of the most prominent events and actors of the revolutionary period." The descendant of founders of New England, Palfrey was born in 1741. A sailmaker's son, he was educated at John Lovell's school in Boston and in the counting house of Nathaniel Wheelwright, a prominent Boston merchant, before entering into trade on his own. In 1764, after John Hancock inherited his uncle's great fortune, he hired Palfrey to assist him in his extensive business affairs, although Palfrey continued to conduct his own business as well. Palfrey's business connection to John Hancock and strong support for resistance to the Stamp Act brought him into contact with the Boston Sons of Liberty. According to his biographer, he was frequently employed as their secretary, in 1768 corresponding with John Wilkes on their behalf. During the years after the 1769 celebration of the defeat of the Stamp Act, Palfrey had a dual career in business and politics. He travelled extensively, visiting New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston on business, but also to coordinate colonial resistance to British rule, and sailed twice to London to confer with friends of the patriot movement, returning to America in the summer of 1775, after the Revolutionary War began.

During the Revolution Palfrey was an aide to General George Washington and then paymaster of the Continental Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He was with Washington in the field at Trenton and the following year at Valley Forge. In November 1780, he was appointed consul-general in France with responsibility for the financial accounts of the United States in Europe. Palfrey "perished in the public service." Shillala, the ship that he embarked on, sailed for France in December and was never seen again. He left a widow, Susan ("Susannah") Cazneau Palfrey, whom he had married in Boston in 1765, and the three surviving of their eight children. His alphabetical list was donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society by Palfrey's biographer--and grandson--the theologian and historian John G. Palfrey, on the centennial of the celebration, 14 August 1869.

The 250th Anniversary of the Stamp Act Riot

On Friday, 14 August 2015, there was a public commemoration of the 14 August 1765 Stamp Act Riot at Liberty Tree Plaza in Boston, between 8:00 and 10:00 PM. As darkness fell, parties of celebrants carried lanterns from five historic locations in Boston to the site of the Boston Liberty Tree, where there were remarks by the organizers of the program. On Saturday, 15 August, there were events to commemorate the more controversial 26 August riot—in the daytime and without threat to the life and property of any government official. For more information on the celebration and upcoming anniversaries of the coming of the Revolution in Boston, see the Revolution 250 website.

Stamp Act Materials on Display

Through 4 September 2015, artifacts and documents relating to the Stamp Act—including surviving examples of the original stamps—will be on display at the Massachusetts Historical Society in an exhibition titled, "God Save the People! From the Stamp Act to Bunker Hill." The exhibition, which tells the story of the coming of the Revolution in Boston, is open to the public without charge, Monday through Saturday, 10:00 AM-4:00 PM.

Sources for Further Reading

Boston 1775, the website created by J. L. Bell, is a goldmine of information about the period and many of the participants in the 1769 anniversary celebration.

Boston Evening-Post. Boston, Mass. 21 August 1769, p. 2.

Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972.

Nicolson, Colin. "Governor Francis Bernard, the Massachusetts Friends of Government, and the Advent of the Revolution." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1991. Boston: Published by the Society, 1992. Vol. 103, 24-113.

Nicolson uses the Palfrey list to determine the names of men who were both "Friends of Government" and "Sons of Liberty."

"An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty who dined at Liberty Tree, Dorchester Aug. 14, 1769." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 1869-1870. Boston: Published by the Society, 1871, 139-141.

Palfrey, John G. "William Palfrey." The Library of American Biography Conducted by Jared Sparks. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1845. Second Series, Vol. II, 337-448.

Tyler, John W. Smugglers & Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986.

John Tyler identifies the Boston merchants who were among the participants in the 1769 anniversary.