Collections Online

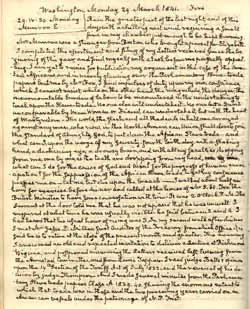

John Quincy Adams diary 41, entry for 29 March 1841, page 292

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- MHS Collecting History

- MHS 225th Anniversary

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Witness to America's Past ]

The world, the flesh, and all the devils in hell are arrayed against any man, who now, in this North-American Union, shall dare to join the standard of Almighty God, to put down the African slave-trade. (FN1)

This entry, written in 1841 by John Quincy Adams in his diary, had its origins in an event that occured two years ealier. In 1839 a group of about fifth Africans who had been illegally kidnapped from their homeland, transported to Cuba, and sold as slaves, revolted against their captors and seized their ship, the Amistad. They intended to sail home but were deceived by the Spanish slave trader crew who covertly steered the ship towards the coast of the United States. The Africans were apprehended by the United States coastal survey ship Washington off Montauk, N.Y., and taken into custody in Connecticut. Two issues were at stake: whether the African captives could be considered "property" and if so, whose claim to "ownership" was valid, that of the Washington's captain or that of the Spanish traders (with the support of the Spanish Government). The complicated diplomatic case of the Amistad captives moved from the district court to the Supreme Court and attracted the attention of abolition and antislavery forces along the way. (FN2)

To bolster their cause, abolitionists Ellis Gray Loring to Boston, and Lewis Tappan of New York, personally appealed to former Philadelphia to former President and current United States Representative John Quincy Adams to assist the defense counsel before the Supreme Court. Adams was reluctant to undertake a courtroom role in the case after a thirty-year absence from the law, but he freely offered to advise the chief counsel, Roger S. Baldwin. Loring and Tappan were not satisfied, however, and Adams finally yielded to their entreties in this critcal case. (FN3) It was not a decision that he made easily; though he was in favor of an end to slavery through constitutional amendment, he was often at odds witht he actions and rhetoric of the abolitionists. It was their appeal to his conscience and his belief in the priciple of habeas corpus that gave him the determination to fight. (FN4)

On 24 February, 1841 John Quincy Adams appeared before the United States Supreme Court to argue the defense of the Amistad captives. Though he approached his appearance with "increasing agitation of mind ... little short of agony," his distress vanished as he began to speak—for eight and one half hours over the course of two days. (FN5) Justice Joseph Story called Adams's argument "extraordinary ... for its power, for its bitter sarcasm, and its dealing with topics far beyond the record and points of interest." (FN6) Adams "waited upon tenterhooks" when the court returned with a decision one week later; Justice Story delivered the opionion that the Amistad captives were free and directed their release from custody. The court refused to consider the Africans as "property," and also reversed the decision of a lower court placing them in custody of the President of the United States to be returned to Africa. (FN7) Adams was elated. With great joy he informed Tappan, "The Captives are free! ... thanks—thanks! in the name of humanity and of Justice to you." (FN8) For the seven years remaining in Adams's life, the congressman continued to resist any expansion of slavery and perservered in the search for a peaceful end to its horrors. He confided to his diary:

what can I, upon the verge of my seventy-fourth birthday, with a shaking hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain, and with all my faculties, dropping from me, one by one, as the teeth are dropping from my head, what can I do for the cause of God and Man? for the progress of human emancipation? for the suppression of the African Slave-trade? Yet my conscience presses me on—let me but died upon the breach. (FN9)

John Quincy Adams kept his diary for sixty-eight years, from November 1779, when he was twelve, to December 1847, just a few months before he died. It consists of fifty manuscript volumes of various sizes, and although it contains gaps and the length of some of the entries is no more than a line, there is a twenty-five year period of full entries with no interruption—an extraordinary feat. Adams reveals his diplomatic and political pursuits along with his personal and family life in this manuscript, which is currently being published in full by the Historical Society and Harvard University Press.

Sources for Further Reading

1. John Quincy Adams, Diary, 19 March, 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.

2. Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Union. New YorK: Alfred A. Knopf,1956, p. 384-393.

3. John Quincy Adams, Diary, 27 October, 1840, Adams Papers, MHS.

4. John Quincy Adams to Charles Francis Adams, 14 April 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.

5. John Quincy Adams, Diary, 23, 24 February and 1 March, 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.

6. Story, William W., ed. Life and Letters of Joseph Story. 2 vols. C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1851, 2:348

7. John Quincy Adams, Diary, 9 March 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.

8. John Quincy Adams to Lewis Tappan, 9 March, 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.

9. John Quincy Adams, Diary, 19 March, 1841, Adams Papers, MHS.