Congratulations! 2012-2013 Graduates Using MHS Materials

By Anna J. Cook, Reader Services

Since July 2012, the Massachusetts Historical Society has granted use permission to a number of scholars utilizing MHS collections in their theses and dissertations. Below are a list of the scholars and their projects.

Many of these projects should be available in the ProQuest database of theses and dissertations. We encourage you to explore the fine work done by our researchers!

“Lost [or Gained] in Translation: The Art of the Handwritten Letter in the Digital Age”

Dallie Clark, University of Texas

“Plain as Primitive: The Figure of the Native in Early America”

Steffi Dippold, Stanford University

“ ‘Rage and Fury Which Only Hell Could Inspire’: The Rhetoric and Ritual of Gunpowder Treason in Early America”

Kevin Q. Doyle, Brandeis University

“Bodies at Odds: The Experience and Disappearance of the Maternal Body in America, 1750-1850”

Nora Doyle, University of North Carolina

“ ‘Deep investigations of science and exquisite refinements of taste’: The Objects and Communities of Early Libraries in Eastern Massachusetts, 1790-1850”

Caryne A. Eskridge, University of Delaware

“Female Voices, Female Action: A Small Town Story that Mirrors the State Struggle to Protect Massachusetts Womanhood, 1882-1920”

Sarah Fuller, Salem State University

“Engendering Inequality: Masculinity and the Construction of Racial Brotherhood in Cuba, 1895-1902”

Bonnie A. Lucero, University of North Carolina

“Trading in Liberty: The Politics of the American China Trade, c. 1784-1862”

Dael A. Norwood, Princeton University

“Het present van Staat: De gouden ketens, kettingen en medailles verleend door de Staten-Generaal, 1588-1795”

George Sanders, University of Leiden

“International Tourism and the Image of Japan in 1930 through Articles and a Travel Journal Written by Ellery Sedgwick”

Katsura Yamamoto, University of Tokyo

Did you, or anyone else you know, author a thesis or dissertation using materials held in the MHS collections in the past year? Please leave a comment on this post sharing the title, author, and the name of the institution to which the work was submitted.

Thank you all for your excellent work!

comments: 1 |

permalink

| Published: Friday, 5 April, 2013, 1:00 AM

Massachusetts Historical Review Volume 14 on Its Way

By Jim Connolly, Publications

It’s the most wonderful time of the year: that time when a new volume of the Massachusetts Historical Review goes to press! Print subscribers will receive Volume 14 by mail in the early days of the new year, and the electronic version will be published simultaneously through JSTOR’s Current Scholarship Program. Learn more about subscription here. The journal is also a benefit of MHS membership—learn more about membership here!

The upcoming volume treats a diversity of fascinating topics:

“Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic” by Amalie M. Kass

Cotton Mather’s advocacy for inoculation—a practice then unheard of in the colonies—stirred up a controversy in 18th-century Boston. Insults and accusations flew in the partisan newspapers as inoculation’s champions and opponents fought for public health—and personal glory. The source of Mather’s knowledge of inoculation may surprise you.

“The Newbury Prayer Bill Hoax: Devotion and Deception in New England’s Era of Great Awakenings” by Douglas L. Winiarski

This article explores the phenomenon of the prayer bill or prayer note in colonial religious practices, and how a satirical prayer bill was crafted to injure the reputation of Newbury Congregational minister Rev. Christopher Toppan, who vehemently opposed the popular religious revivals of the Great Awakening.

“A Prince among Pretending Free Men: Runaway Slaves in Colonial New England Revisited” by Antonio T. Bly

Bly sheds light on the lives and characteristics of runaway slaves through in-depth analysis and explication of runaway notices in newspapers. Clues within these notices tell us how fugitive slaves employed quick wits and savvy under extraordinary duress. Bly, who has compiled a database of runaway slave notices, crunches the numbers on a variety of characteristics, illuminating the most common months for escape, the race, linguistic ability, and work backgrounds of runaways, and more.

“Boston, the Boston Indian Citizenship Committee, and the Poncas” by Valerie Sherer Mathes

When the Ponca Indians of Nebraska were forced from their homeland in 1877 and sent to the inhospitable Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), many Americans sympathized with their plight. Among those who took up the cause was the Boston Indian Citizenship Committee, a group of philanthropists, described in detail for the first time in this article. Mathes also chronicles the speaking tours in support of the Poncas, including the tour of Ponca chief Standing Bear.

The new volume also includes review articles by Sarah Phillips and Chernoh Sesay concerning environmental history and books about Phillis Wheatley and Venture Smith, respectively.

Every issue of the MHR offers pieces rich in narrative detail and thoughtful analysis, and Volume 14 is no different. The MHS looks forward to its publication.

comments: 0 |

permalink

| Published: Friday, 30 November, 2012, 1:00 AM

Bostonians Respond to Union Loss at 2nd Bull Run

By Jim Connolly, Publications

31 August 1862 was a remarkable day in Boston—one full of anxiety and activity. News reached town that day of the Union’s devastating defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run. The battle, which took place in Virginia from 28 to 30 August, resulted in approximately 15,000 casualties, the vast majority suffered by Union soldiers. Bostonians responded with a diligent relief effort.

Nothing in the historical record captures the mood of such a moment like a good diarist. Caroline Healey Dall (whom I’ve blogged about before) was an excellent one, and her journal, which lives at the MHS, gives us a bracing account.

I heard Mr Clarke preach, yet hardly heard him, for I longed for the service to be over, that I might hurry home to help prepare lint & bandages.

....

No one who was in Boston today—will ever forget it. No one but will be proud to own it as a birth place. The car which I took from Dover St. to Court—was crowded to a crush with women & bundles. Most of them were weeping. "Give way," said rough men to each other, "those bundles are sacred." When we got to the Tremont House—a dense crowd had pressed between it & the Hall. All were eagerly gaping for rumors. About the Tremont Temple a semi-circular rope was stretched enclosing several hundreds of cubic feet. At Three Tables, placed in the center & at each end, men took down subscriptions for the freight fund. Within on the side walk immense boxes were being packed. In the building 1800 women sewed all day.

....

In the car that went to Medford every body was bitterly depressed. The women thought—that if we conquered in the end, the life of the Camp would ruin our young men, that they would come home coarse, licentious cruel. I could not stand this, and the end was, that I appealed aloud to the women, in a plea lasting—partly in a conversational way, nearly the whole time we were coming out, as to the moral end of the war. How moved the whole population were we can judge from the fact, that one could hear a pin drop in that rattling car—& there was not a smile at me on man's or woman's face.

If the news of the Second Battle of Bull Run and the mad rush to send relief were not cause enough for emotional turmoil, the day held yet another significant—and personal—event for Dall. That morning, her husband, the Unitarian minister Charles Dall, arrived in the ship Panther from Calcutta, where he had been engaged in missionary work since 1855 and where he would live until his death in 1886. This was the first of his four trips home over 31 years. But in the confusion of the day, their paths did not cross.

Willie came out at dusk to tell me, that his father would not get up till tomorrow. I was surprised to find that in the general distress, I had forgotten my private pain, not having thought of the Panther, after thinking of nothing else for months, since I heard she was in the bay.

To learn more about Dall and her materials at the MHS, check out the Caroline Wells Healey Dall Papers 1811-1917: Guide to the Microfilm Edition. We are pleased to work with editor Helen R. Deese to produce the four-volume Selected Journals of Caroline Healey Dall, of which Volume I (1838–1855) is available and Volume II (1855–1866) is in preparation. The excerpts above are taken from the 31 August 1862 entry in volume 25 of Dall’s journals, which covers 24 April 1860 to 23 October 1862, and the full entry will appear in Volume II of Selected Journals.

comments: 0 |

permalink

| Published: Friday, 31 August, 2012, 8:00 AM

Interview with Author and NEH Fellow Martha Hodes

By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

Martha Hodes, author of The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth Century, is the recent recipient of an NEH fellowship to conduct research at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The Sea Captain’s Wife was a finalist for the Lincoln Prize and was named a Best Book of 2006 by Library Journal. Hodes, who teaches at New York University, took the time to talk with us about the book, her past research, and her current project.

Martha Hodes, author of The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth Century, is the recent recipient of an NEH fellowship to conduct research at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The Sea Captain’s Wife was a finalist for the Lincoln Prize and was named a Best Book of 2006 by Library Journal. Hodes, who teaches at New York University, took the time to talk with us about the book, her past research, and her current project.

1. How did you come to know the Society and become involved in research here?

I first conducted research at MHS while I was writing my second book, The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth Century. The book’s protagonist, Eunice Connolly, is a white, working-class woman from New England whose husband fought and died for the Confederacy – after which she married a black sea captain from the Caribbean. Manuscript collections at the MHS illuminated important context, including anti-slavery sentiments in the New Hampshire town where Eunice lived during the Civil War, and anti-Irish sentiments in the cotton mills (where Eunice worked). Eunice lived in Lowell when the war was ending, so I also invoked a Lowell woman’s personal response to Lincoln’s assassination from the Martha Fisher Anderson Diaries at MHS. I had no idea then what my next book would be about.

2. What is the focus of your research during your NEH fellowship?

I’m writing a book, Mourning Lincoln, about personal responses to Lincoln’s assassination, encompassing northerners and southerners, African Americans and whites, soldiers and civilians, men and women, rich and poor, the well-known and the unknown, those at home and abroad. I’m specifically searching beyond the public and ceremonial record in order to move beyond the static portrait of a grieving nation that we find in headlines and sermons. The idea is to understand a transformative event on a human scale -- access to the hearts and minds of individual Americans across the spring and summer of 1865 tells us so much more than we thought we knew.

3. How did you become interested in history and decide to enter this field?

I went to college sure I’d be an English major. At Bowdoin, I ended up creating a double major in Religion and Political Theory. Then I continued my studies in comparative religion by getting an MA at Harvard Divinity School. During those years, my work-study job was at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, and that was where I came to see that I was happier immersed less in abstract ideas and more in the workings of people’s daily lives. That’s when I applied to PhD programs in History.

4. What inspired you to write The Sea Captain’s Wife? Did you discover anything unexpected while writing it?

While writing my dissertation at Princeton, I came across an amazing collection at Duke University – the letters of Eunice Connolly’s family. They didn’t belong in my dissertation and first book (White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the Nineteenth-Century South), because Eunice’s story wasn’t a southern one, and I hoped no one else would discover the collection before I got to it. Lucky for me, no one did. And the letters did indeed yield unexpected discoveries -- about race and racial classification. I found that when Eunice worked as a laundress during the Civil War (that was the lowest of lowly domestic work, reserved for Irish immigrants and black women), her New England neighbors barely thought of her as a white woman, and her subsequent marriage to a man of color further justified her exclusion from white womanhood. Then, when Eunice married the sea captain and went to live in the Cayman Islands, her neighbors there came to think of her as a woman of color, but in a very different way. In the Caribbean racial system, where the category of “colored” lay closer to whiteness than to blackness, Eunice’s status -- as the wife of a well-to-do sea captain of African descent -- rose beyond anything she had known as a poor white woman in New England. All in all, Eunice’s life story illuminates not only how malleable are racial categories and their meanings, but also how much power those classifications can hold. I didn’t know any of that when I began to write her story from the letters.

5. A number of professors have used The Sea Captain’s Wife in undergraduate and graduate-level courses. How do you feel about your work being taught and what do you look for in selecting materials for your own students?

I wrote The Sea Captain’s Wife for readers both within and beyond the academy, and I’m equally thrilled when professors assign it in their classes as I am when it’s chosen by, say, a women’s reading group. In my own classroom, whether I’m teaching conventional courses (like the Civil War or Nineteenth-Century U.S. History) or less conventional courses (like Biography as History or History and Storytelling), I strive to assign books that both impart good history and illuminate people’s lives, by asking -- or prompting the students to ask -- big questions about both the past and the present. I’m happy if The Sea Captain’s Wife can accomplish some of that. It’s what I hope to accomplish, too, in Mourning Lincoln.

comments: 0 |

permalink

| Published: Wednesday, 1 August, 2012, 8:00 AM

New Biography Illuminates Life of Clover Adams

By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

For all the importance and notoriety of Henry Adams’s book The Autobiography of Henry Adams, it contains one glaring omission: Henry’s wife Clover Adams is not mentioned once. Natalie Dykstra’s new biography, Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, attempts to rectify this by shedding light on the life and work of a remarkable 19th-century woman. This is no dry, esoteric biography, but an engaging, enjoyable read for the scholar or layperson alike.

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

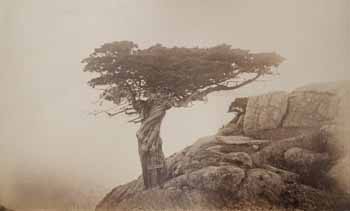

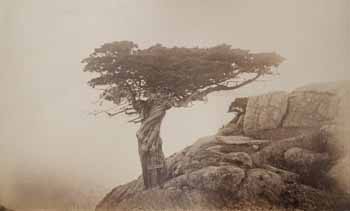

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

In the spring of 1885, Clover’s father died, and her emotional state worsened. In December of that year she took her own life by drinking a chemical used in processing photographs. She was 42 years old. Although Henry Adams rarely spoke of his wife after her death, he commissioned the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to produce a memorial at her gravesite in Rock Creek Cemetery. Saint-Gaudens created a sculpture of a mysterious shrouded, seated figure, which still receives many visitors today and helped inspire Natalie Dykstra to begin researching this book.

Dykstra is an associate professor of English at Hope College in Holland, MI, and she received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship for her work on Clover Adams. A Fellow of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Dykstra did much of the research for her book at the Society, and she guest-curated the Society’s current exhibit, A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life: The Photographs of Clover Adams. The exhibit is free and open to the public and runs through June 2nd.

comments: 0 |

permalink

| Published: Friday, 25 May, 2012, 8:00 AM

older posts

Martha Hodes

Martha Hodes Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children. Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.